Curated by Philip Tinari and Guo Xi

John Gerrard’s first exhibition in China featured Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada), Farm (Pryor Creek, Oklahoma) and Exercise (Dunhuang) recently shown at UCCA in 798 , Beijing.

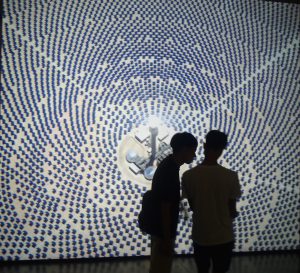

Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada) John Gerrard, POWER.PLAY at UCCA, 798, Beijing Summer 2016

What is real and what is a real representation are some of the internal workings going on with you as you experience these huge simulated light sculptures. These ambiguous interventions are so very similar to camera work. The slow steady panning of movement is quite hypnotic and the viewer needs time to find out how they are responding to this slightly strange yet familiar world.

But there are many layers to this new media and lucky for me Gerrard is one of the most articulate artists I have come across.

These pieces of software do not exist if they’re not energized. “The works are effectively energy in transit. That’s their condition. There is no film. There is no artifact. You simply have this set of instructions, which is bundled into an executable file. Without a computer to execute it, you have nothing. So my logic around that is that this is a very pregnant way to respond to contemporary conditions, because a lot of our realities are profoundly influenced by what I would call the algorithmic turn. Investment banking, political decision-making, military decision-making, trade, supermarkets: they are modeling reality, and, on that basis, they are making decisions about how reality is formed.”

Usually when you think about time based media you think of a fixed time for a particular work however Gerrard’s work is exported as software which produces a non durational image in real time. Assistant curator Guo Xi elaborated, “the non durational emphasizes how it is different from video as the software is variable into time zones, season, changing daylight and so the time factor reaches far beyond the idea of a fixed time for which the artwork lasts.”

Often exploring geographically isolated locations, Gerrard has pioneered the use of post-cinematic, virtual space through complex algorithms that generate imagery in real time often referring to structures of power and networks of energy that have coincided with the expansion of human endeavor in the past century.

The game engine Gerrard uses is a Russian engine called Unigine which builds a virtual world around a camera position. After taking a huge number of images which are then sent to a 3 D modeler who rebuilds a 3 D portrait of the building or area of interest, a process which often takes more than a year. This production can’t be automated and is built “by hand” building up small sections of complicated buildings. Once the model is completed to satisfaction it goes into the game engine creating a somatic world in a virtual space.

It needs a powerful machine, like a gaming-type machine. It can be manifested as a projection, it can exist as an object, it can exist as an LED wall. For this exhibition they are projections (from behind ) on expansive screens 4 by 5 metres in size sponsored by video equipment Christie. The only place that it really cannot exist is online because the scenes are too dense.

Solar Reserve is a piece of software that simulates a massive light sculpture of a powerplant in the Mojave Desert. It was exhibited at the Lincoln Center Plaza, New York in 2014. The sun is programmed for a solar annual orbit of 365 days, so that piece is an annual work—the sun rises and falls in real time. And so the camera view tracks a 30 minute from ground to space and another 30 mins returning back down to grounds taking 12 hours to do one cycle. These orbits around the solar plant is a symbol of humanity’s reliance on and resistance to solar rhythm.

Exercise (Dunhuang) 2014,

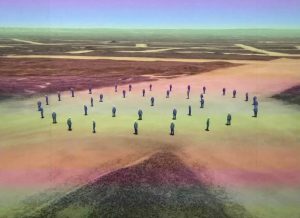

Exercise is a reconstruction based on satellite imagery of a network of roadways the size of a small town located mysteriously in the middle of the Gobi Desert, which then becomes the site for a lengthy elimination game played among avatars modeled on factory workers in Guangzhou.

Gerrard applied motion scans of 38 workers from a Guangzhou computer manufacturing plant, wearing blue uniforms and paper bonnets, into the simulation, their movements as they wander through the vast network mirroring those of the actual workers.

The scanning for this alone took a year of work, after the layout of the roads, then figures for the “Game” and recording their individual movements and the manner in which they may fall during the game once they see another figure (ie once another figure comes into view on the screen).

Exercise (Dunhuang) 2014, John Gerrard, POWER.PLAY at UCCA, 798, Beijing Summer 2016

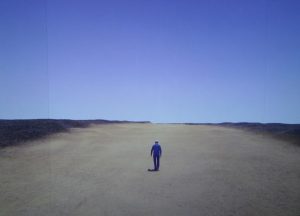

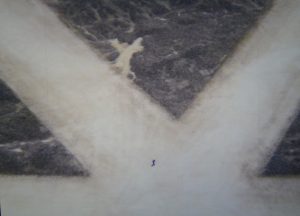

One screen showed a simulation of a satellite camera (you can barely make out the slowly moving dot of a figure), the other of a simulated view from a drone and the third of a camera on the ground focused on the nearby figure. Only one figure is documented at a time and that is the figure holding the view of the camera. The image above was taken just at the start of the game when all 39 figures are in view this only happens once every 3 days while the game lasts.

Exercise doesn’t have human participants but virtual participants. Gerrard pointed out the inhuman link to the work. “You can deal with much more when working with inhuman durations, inhuman requests with 38 factory workers who perform through night and day, over an annual orbit, with no rest, with no food, with nothing that would be considered normal working conditions. So there’s a kind of cruelty within it, but it’s sort of a victimless crime in a way.”

Exercise (Dunhuang) 2014, John Gerrard, POWER.PLAY at UCCA, 798, Beijing Summer 2016 (ground view)

Even though there is a logical method to the game you are following the expected order of events are without emotion and so the viewer is dislocated from the outcome. Which ever figure is nearest an exit and is within view of another person, that figure falls down and is removed from the game.

The roadways are cleared gravel revealing a pale substrate sad underneath. “I think it’s interesting to pick up Land Art as a virtual form and present it to the public in the form of light interventions”

The whole nature of this game and the location from which it was designed reflects military readiness and preparedness.

Exercise (Dunhuang) 2014, John Gerrard, POWER.PLAY at UCCA, 798, Beijing Summer 2016 ( simulated drone view)

“The work rests on traditions of military simulation, ie battlefield simulations, flight simulations—that is its history. …. battle play, which were early strategy games, sandbox games, where military strategists would play out outcomes and military campaigns. During what was called the Manhattan Project in America during the Second World War, those types of games were computerized. Some of the very earliest simulations were actually the Manhattan Project’s military strategies models.”

Exercise (Dunhuang) 2014, John Gerrard, POWER.PLAY at UCCA, 798, Beijing Summer 2016 (simulated satellite view)

Gerrard referred to how military readiness is evident in our present times as he spoke at a floor talk at his opening at UCCA. A few days previously (June 2016) the huge military exercise “Anaconda” in Poland took place where 31,000 service members from 24 Nato and partner nations engaged in military exercises to reassure the east European nations rattled by Russia’s actions in nearby Ukraine. Needless to say that uneasy readiness also became more evident the following month after the exhibition opening with Sino-US tensions over the South China Seas brought the work closer to home and very relevant.

Farm (Pryor Creek, Oklahoma)

Farm (Pryor Creek, Oklahoma) 2015, is a digitally modeled composite of one of Google’s server centres in Oklahoma. Here the internet is solidified to metal and concrete an austere industrial unit. The slow panning of a simulated camera movement renders a harshly sunlit industrial exterior with coolings units for the computers. While viewing this you are aware that inside sits one of Googles 6 main data farms. When looking at this themes of power, information and ownership are hard to escape. Other themes which come to mind of input/ output ie the input of all your emails and searches, this is where they are sorted. Some of this information is “output” back to you but it is also output back to other destinations too.

Farm (Pryor Creek, Oklahoma), John Gerrard, POWER.PLAY at UCCA, 798, Beijing Summer 2016

It is that shake free camera work that reminds you that this is a simulation of a reality using algorithms and not a real camera working, sometimes as a viewer you need to remind yourself of this. When Google refused Gerrard access to the plant, he checked with Oklahoma police and hired a helicopter and photographer to document the structure from above (4 to 5 thousand photos)so that a sufficient number of images were processed to rebuild the virtual building.

So what are we looking at is a virtual representation of a real place which processes and exchanges virtual information bringing the internet down to bricks and mortar and metal.

What interests Gerrard most with this building is what powers it. “I was interested to root the internet in this one particular site, that it’s not an ethereal, otherworldly entity. It has a presence on the landscape and by documenting these great diesel generators it is clear that this (Google) is a diesel-powered website. Data is energy in transit…It doesn’t just exist ethereally…..The building is actually a minimal object in a sense, but it’s full of power. It’s not a void. It has 40,000 computers in there.”

with John Gerrard just before he legged it out the door

Note: This post makes reference to the content of the Peckham-Gerarrd interviews published by UCCA 2016.